What is Delayed Wound Healing?

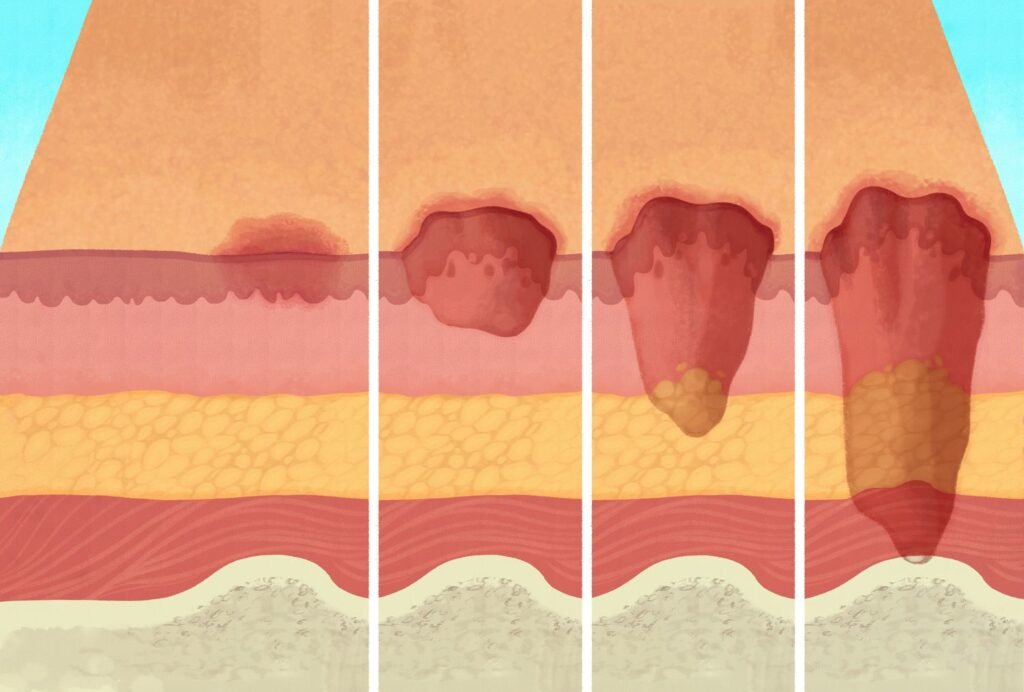

Daniel Davidson, MD, MBA, DBA, PHD Introduction: The physiological process of wound healing is intricate and includes several phases, such as tissue creation, remodeling, and inflammation. Most of the time, wounds move through these phases quickly, resulting in a successful closure and the preservation of tissue integrity. But occasionally, the healing process could take longer than expected, which could present difficulties for both patients and medical professionals. Numerous variables, from underlying medical issues to environmental circumstances, can cause delayed wound healing. We examine the reasons, signs, and available treatments for delayed wound healing in this article. What is Delayed Wound Healing? A condition known as “delayed wound healing” occurs when the body’s normal healing process—which normally involves mending damaged tissue—takes longer than anticipated or does not proceed through the phases in a reasonable amount of time. The biological process of wound healing is intricate and includes tissue creation, remodeling, and inflammation. In most cases, wounds close successfully and tissue integrity is restored as they move through these phases in a timely manner. Delays can occur from a variety of circumstances interfering with the natural healing process. These could include underlying medical disorders that affect blood flow, weaken the immune system, or obstruct the supply of vital nutrients needed for tissue regeneration, such diabetes, vascular disease, or malnutrition. Another frequent reason for delayed wound healing is infection, which is brought on by microbiological invasion, which can also worsen tissue regeneration, lengthen inflammation, and raise the risk of consequences. Causes of Delayed Wound Healing: A number of things can cause delayed wound healing, and all of them can make it more difficult for the body to restore injured tissue. These are a few typical reasons: Underlying Health Conditions: Wound healing can be severely hampered by long-term conditions such diabetes, vascular disease, autoimmune disorders, and malnutrition. These ailments may weaken the immune system, impair blood flow to the wound site, or obstruct vital nutrients needed for tissue healing. Infection: Infected wounds have a higher probability of taking longer to heal. Infections with bacteria, fungi, or viruses can exacerbate tissue regeneration, prolong inflammation, and raise the possibility of consequences including sepsis or abscess formation. Inadequate Blood Supply: To support tissue regeneration and healing at the wound site, enough blood flow is necessary to deliver nutrients and oxygen. Healing can be hampered by conditions that impair blood supply, such as venous insufficiency or peripheral artery disease. Drugs: A number of drugs have the potential to obstruct the body’s natural healing processes, delaying the healing of wounds. Corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are a few examples. Smoking: By narrowing blood vessels, lowering oxygen flow to tissues, and compromising immunological function, tobacco use can hinder the healing of wounds. Smokers are more likely to experience problems after surgery or an injury, including delayed wound healing. Advanced Age: Aging is linked to alterations in the structure of the skin, a decrease in the generation of collagen, and a compromise in immunological function, all of which can cause delays in the healing of wounds. Nutritional Deficiencies: Encouraging the body’s healing processes requires a healthy diet. Wound healing can be hampered by deficiencies in protein, vitamins (especially C and A), and minerals (such iron and zinc). Obesity: Carrying too much weight around can put strain on wounds, obstruct blood flow, and raise the possibility of problems like infection. Poor outcomes after surgery or injury and delayed wound healing are linked to obesity. Poor Wound Care: Inadequate wound care can slow down the healing process and raise the risk of complications. This includes inappropriate cleaning, dressing selection, and failure to shield the site from additional trauma or infection. Symptoms of Delayed Wound Healing: Persistent Redness: Prolonged redness or inflammation in the vicinity of the wound may be a sign of continued inflammation and poor healing. Swelling: Prolonged edema or swelling close to the wound site may be a sign of a delayed healing process, which is frequently brought on by fluid buildup and poor lymphatic drainage. Warmth: If the skin around the incision feels warmer than the surrounding skin, there may be persistent inflammation and insufficient healing taking place. Pain: Continued or worsening pain at the site of the wound, especially during the initial phases of healing, may be a sign of underlying problems such tissue damage, nerve involvement, or infection. Increased Drainage: Extended periods of significant pus, blood, or clear fluid drainage from wounds may be a sign of infection or delayed healing. Reopening of the Wound: After first closure, wounds that frequently deteriorate or reopen may be a sign of underlying problems with tissue regeneration and healing. Development of Granulation Tissue: A symptom of the healing process, granulation tissue takes the form of pink or red tissue in the wound bed. On the other hand, extensive or protracted granulation tissue production could be a sign of postponed healing. Symptoms throughout the system: Systemic symptoms like fever, chills, weariness, and malaise can appear in severe cases of delayed wound healing, especially if an infection is present. Treatment of Delayed Wound Healing: Wound Debridement: Objective: By minimizing the chance of infection and establishing a clean wound bed, removing dead or necrotic tissue from the wound site aids in the healing process. Techniques: There are a number of ways to accomplish debridement, including as mechanical, enzymatic, autolytic, or surgical approaches. Procedure: Depending on the features and severity of the wound, medical professionals will carefully remove non-viable tissue using sharp instruments, specialty dressings, or topical treatments. Infection Control: Objective: In order to lower inflammation, avoid systemic problems, and encourage tissue regeneration, it is essential to treat underlying infections. Method: Depending on the kind of infection present and the outcomes of culture and sensitivity testing, medical professionals may recommend antimicrobial therapy, such as antibiotics, antifungals, or antivirals. Monitoring: Treatment choices are based on a routine evaluation of the site for indicators of infection, such as elevated redness, edema, temperature, or purulent drainage. Optimizing Nutrition: Objective: By giving the body the vital